The biggest challenge I face is that I am tasked with creating inclusion opportunities for several students who are in a substantially separate classroom for students with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Although I have taught students with autism before, I have never worked with students who have this level of disability. I have been making a LOT of mistakes and, most of the time, learning from those mistakes.

Sometimes I bring a few of the students from the ASD classroom upstairs to the second grade general education classroom. This is hard, though, because it is a small, crowded, relatively noisy room. I feel a little claustrophobic and distracted with the extras kiddos in there, so I can only imagine how they feel.

Other times I bring between 4 and 10 students from both classrooms (the ASD room and the general ed room) into the Learning Center, where we either do the same lesson they are doing in the classroom, or a variation on it, or a variety of centers.

But the best part of my week is the 50 minutes on Mondays when I bring four students from the second grade general education class downstairs to the ASD classroom. They pair up with four students with autism for Counting Collections.

I bring different students down most weeks, so that everyone has a chance to go, but some students go more often than others -- because I want them to build off what they did the week before, because I think they need the counting practice, or because they are really, really good at being partners with their special education peers.

(A note on language: I wish that we had names for our classrooms that were, say, animal names, instead of calling them "second grade general ed" and "the ASD classroom," but we don't. Soon I'll introduce you to a few of the students and call them by name because it is both unwieldy and somewhat distasteful to call them the "general ed students" and the "special ed students.")

A few weeks ago, I paired Ricky up with Elena to be counting partners. Ricky is a second grader with ASD. He is working on matching quantities to numerals and counting quantities under 30. He is a quiet guy, but he does communicate verbally and understands a lot of what is said to him. Elena is in the general education second grade class. I had noticed her having some hesitation when counting under 100 (pausing at a new decade, for example), and she needed practice with making groups of ten and understanding place value.

Ricky and Elena chose a collection of links. There were 46 links in the collection. The first time I checked in with them, they were lining up the links and counting by ones. I saw Elena doing most of the counting, so I asked her to stop and let Ricky count, telling her she could help him if he got stuck or made a mistake. He paused for several seconds at each new decade after 20 and sometimes needed help remembering what came next as he counted.

The first time they counted, they got 39 links. I commented on how they had organized the links, and asked them to recount so I could see how they counted. This time they got 46.

"How can you be sure it's 46 and not 39?" I asked. They both looked at me for awhile. Then Elena started to count again. She counted one link twice and got 47.

"Is there a way you could organize them so they would be easier to count accurately?" I asked.

I have a variety of tools they can use for organizing: ten frames, cups, and plates. They chose cups, and started to put two links in each cup.

When I came back, they had 2 in each cup and had put the cups into groups of 4 cups (8 links), with one group of 3 cups (6 links).

"It's 46," Elena said.

"Did Ricky help count?" I asked.

"Sometimes," she answered.

"Show me how you figured out it's 46," I said.

She counted them by ones. She got to 30, then counted one more group of 8 (by ones), miscounted, and got 39. "So 30 plus 8 is 39?" I asked.

She thought for a few seconds and said, "No! It's 38." She recounted them to be sure, then continued on to 46.

I suggested they label each group with the total they had after counting that group. Elena re-counted and I asked Ricky to make the labels. He used a hundreds chart to find the numbers to write. He could find numbers like 38 and 46 but didn't know how to write them on his own. He wrote carefully, clearly, and proudly.

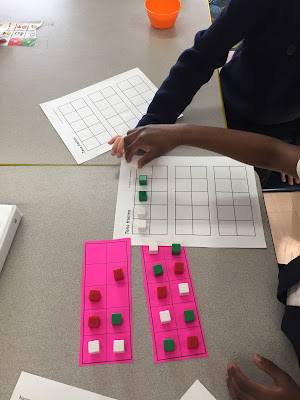

By that point, time was up. Between Elena and Ricky and the other pairs working that day, we had a variety of grouping strategies. Several had grouped by tens, and one pair had made groups of four. Here are a few photos of their work.

I decided the next week to share some of this work with the whole group. One of my goals was to encourage students who had not grouped by tens to think about the advantages of doing so.

The next week, I started class by saying I wanted to tell them a story. I had a slideshow of Ricky and Elena's process, and how they had gone from counting all in one big line to grouping in cups and labeling their groups. At the end I included a few other pictures, including the recording sheet showing the groups of ten. Many of the same students were back again (like Elena, who I partnered with Ricky again), but a few were different. Some students were interested in my "story" and the pictures. Others didn't seem to be paying much attention.

I asked which way of counting they thought would be more efficient and accurate: counting by 2s, 4s, or 10s. A few said they thought ten was quickest and therefore they were less likely to make mistakes. Seeing the recording sheet also gave them, I hoped, ideas for how to record their counting.

I showed them the collections of objects they could choose to count and the visual directions (below), reminded them of the options for recording sheets, and sent them off with the partners to start. (Thanks to Chelsea Schneider for ideas for recording sheets, and to Pierre Tranchemontagn for the photo of a simple recording strategy for my visual.) That day, a few teachers from another district were visiting, so I benefited from their extra eyes and ears -- they got to see things going on that I missed.

Elena and Ricky chose to count links again (they like them!), and they had a bigger collection. Here is how they grouped them:

Tens!

And here is Elena's recording of her counting:

Ricky was less involved this time -- he kept hiding links and playing with them, while Elena patiently (or sometimes not-so-patiently) coaxed him back into counting.

After counting, I asked Elena how she would group her collection next time. She said she would try by 4s. So she's not sold on 10s yet.

Lily had come from the general education class as well that day, and she worked with Nick. Lily and Nick get along really well and love working together. Lily suggested they count their collection by twos. Nick didn't know how to count by twos. I came upon them to find her teaching him to count by twos using a hundreds chart. He circled the numbers as they counted together. I didn't watch them for long, but our visitors commented that they could see Lily deepening her understanding of skip counting as she explained it to Nick.

One more piece of work from that day (or it may have been the next week, I'm not sure). This shows the potential of Counting Collections to push students wherever they are in their understanding of number and operations.

What I've noticed and learned:

It is good to offer a lot of choices. I try to bring some familiar and some new objects to count each week. I have larger collections and smaller ones. There are three recording sheets to choose from (the two linked above, plus a sheet with 3 ten frames on it). Partners don't have to choose the same recording sheet. I suggest that the pairs decide together what they would like to count, or I encourage the student with autism to make the choice. They struggle more with attending and being engaged, so I want them to choose an object to count that they enjoy.

2. Collection size

One of my questions when I started Counting Collections with heterogeneous pairs was what size the collections should be. Most of the students with autism are working on counting up to 30 or just above 30. Most of the other students would do well to count larger collections, up to 100 or above 100. I asked on Twitter for advice, and the consensus was to ask each pair to count two collections, a smaller one and a larger one. In practice, I have found that some pairs don't get to two collections in one period, but if they count a collection between 40-60, it seems to be a good challenge for both members of the pair (as in the case of Elena and Ricky).

On one branch of that Twitter thread, Kristin Gray and I discussed recording, and agreed that if students counted more than one collection, they could choose just one to record on paper, and attempt to explain the larger collection verbally if it was a challenge.

In reality, I need an even more flexible definition of recording. On the first day Elena and Ricky worked together, Ricky's recording was figuring out how to write the numbers for each group as they counted. On another day, he was able to show how they counted a much smaller group on paper (pardon the water spill):

One student in the class communicates using a communication device, mostly one word at a time. For him, recording means finding the total on a hundreds chart. With a significant amount of help, he can draw a small collection on paper. Figuring out the best way to make Counting Collections work for him is a challenge I am still working on.

3. Everyone is learning.

My primary goal for this time is that both members of each pair are learning. I have worried from time to time that the students with autism might not get much out of the work if their partners do too much for them. But I have seen partners working together well -- helping each other count, sorting and organizing together, working together to record. With some suggestions from me, they often both have a challenge that pushes their thinking.

Our visitors were most impressed at how much the general education students were learning. One assumption about heterogeneous pairs like this is that the general education students will help the special education students and not be challenged themselves. (I hear this thought often as my school discusses increasing the amount of inclusion we will do in the future.) Because of the low-floor, high-ceiling nature of the task and the many choices involved, most of the time this does not seem to be a problem. One student deepens her understanding of counting by twos, another gains fluency with counting, others build their understanding of our system of tens, and another works on multiplication. It is really exciting to watch.

4. Don't micromanage.

The first week or two, I was obsessed with making sure everyone was productive at all times. I couldn't engage in deep listening or conferring because I was trying to get Chima to stop rolling shapes across the table and dropping them on the floor, or I wanted to be sure everyone was accurately recording their counts on paper. I rushed from pair to pair and never stayed in one place for long.

I soon realized I was spending my time talking about following directions and not math. I stopped trying to make sure everyone was moving forward all the time. Instead, I confer with pairs about their counting (Kassia Omohundro Wedekind has shared some great resources on conferring during Counting Collections) and let go of needing everyone to be productive at all moments. It turns out many of the students are working and thinking whether I'm on top of them or not. And if others aren't, I'm okay with that. It's more important that I have real conversations about the math.

5. Let partners do the work

Related to the last take-away is that fact that the heterogeneous partners can do a lot to keep each other moving. Sometimes they go in unexpected directions. Sometimes one of the pair ends up doing most of the work. But often they nudge and support each other beautifully. This frees me up to do the kind of conferring I want to do.

The last time I led this group, I tried Choral Counting with them. I'm eager to gradually add that in as part of our routine and see where it takes us. Then I'll be thinking of what other low-floor, high-ceiling tasks can meet all of these learners where they are. Send me your ideas!

I think asking students to count out a certain number has benefits too. It still requires Ss to think about how they organize the objects to help them keep track, especially when it is a larger number. And what I have experienced, at least in the beginning, is Ss will resort back to counting by ones up to the number. What I will do purposefully is interrupt these Ss which causes them to loose track and start over:) Whereas when Ss organize their counting, especially when it's by 10s, they quickly can catch up to where they left off when being interrupted. Pictures can be taken of there collection as their recording of the amount they counted. Pictures can also be compared to determine which organization is easiest to tell if they have counted the right amount? Ex: If Ss have counted 37 and there is a picture of 37 in one line, 37 in cups with 2 in each, 37 in ten frames, etc.

ReplyDelete