In the 2018 American Educational Research Association Presidential Address entitled “

Just Dreams and Imperatives: The Power of Teaching in the Struggle for Public Education,” Deborah Ball describes the many “discretionary spaces” a teacher faces each day in her classroom. As Ball explains, teaching is a “highly idiosyncratic and individual” practice in which teachers must make in-the-moment decisions dozens if not hundreds of times a day -- decisions which cannot be mandated by a curriculum or supervisor.

Ball shares a brief video of one minute and twenty seconds in her classroom, in which she identifies twenty discretionary spaces. That’s how often teachers have to make decisions about seemingly minute things such as who to call on, what to say to a student who calls out, how to respond to an incorrect answer, and so on.

Ball explains that it is through these discretionary spaces that racism, sexism, and all kinds of oppression enter our classrooms. While teachers can reinforce bias through their classroom interactions on a daily basis, often without realizing it, they can also use discretionary spaces to begin to free students from racist and sexist stereotypes and roles. This is not easy to do, however, as all of us are steeped in the culture of white, male supremacy -- it’s the air we breathe every day.

One of Ball’s points is that teachers can use discretionary spaces to begin to build new narratives for children of color, girls, and other marginalized or low-status students, and we can do this by “taking as axiomatic the brilliance of Black children.” This is not enough, however, as teachers also have to have “something else to do,” rather than the traditional teaching moves we’ve absorbed through teacher education, formal and informal mentoring, and the “

apprenticeship of observation.”

In the

video from her classroom, Ball shares an example (and you really, really should take the time to watch if you haven’t yet -- her speech starts at minute 46:45, and this part happens at 1:23:05) in which one of her students, Toni, a Black girl, calls out a question without raising her hand, laughing and playing with her hair as she speaks. Ball shares the ways most teachers would respond to Toni (chiding her or ignoring her), and then she offers an alternative: she publicly asserts that Toni’s question is mathematically important, and she asks another student to reply to Toni’s question. In this way, Ball gives everyone in the class, including Toni herself, a moment of seeing “Black girl brilliance” (rather than seeing a Black girl get in trouble for calling out).

Recently, I had the pleasure of watching a white fourth grade teacher, Ms. Lynn,* lead her class in a forty-five minute long math discussion in which they asked each other questions, experimented with ideas and explanations, and explored ideas about multiplication and division. A seemingly trivial question from one student set them off on this unplanned conversation, turning what was meant to be a 15 minute number talk into the entire math class.

Here’s what happened. See what connections you can make between how Ms. Lynn handled this student’s question and Ball’s discussion of discretionary spaces.

Math class started in Ms. Lynn’s room with students partnering up and tossing a large, soft ball back and forth, counting by 3s as they tossed. The goal was to set a new record for the class, counting as high as possible before dropping the ball. The vibe in the room was lovely: energetic but calm, focused, and collaborative.

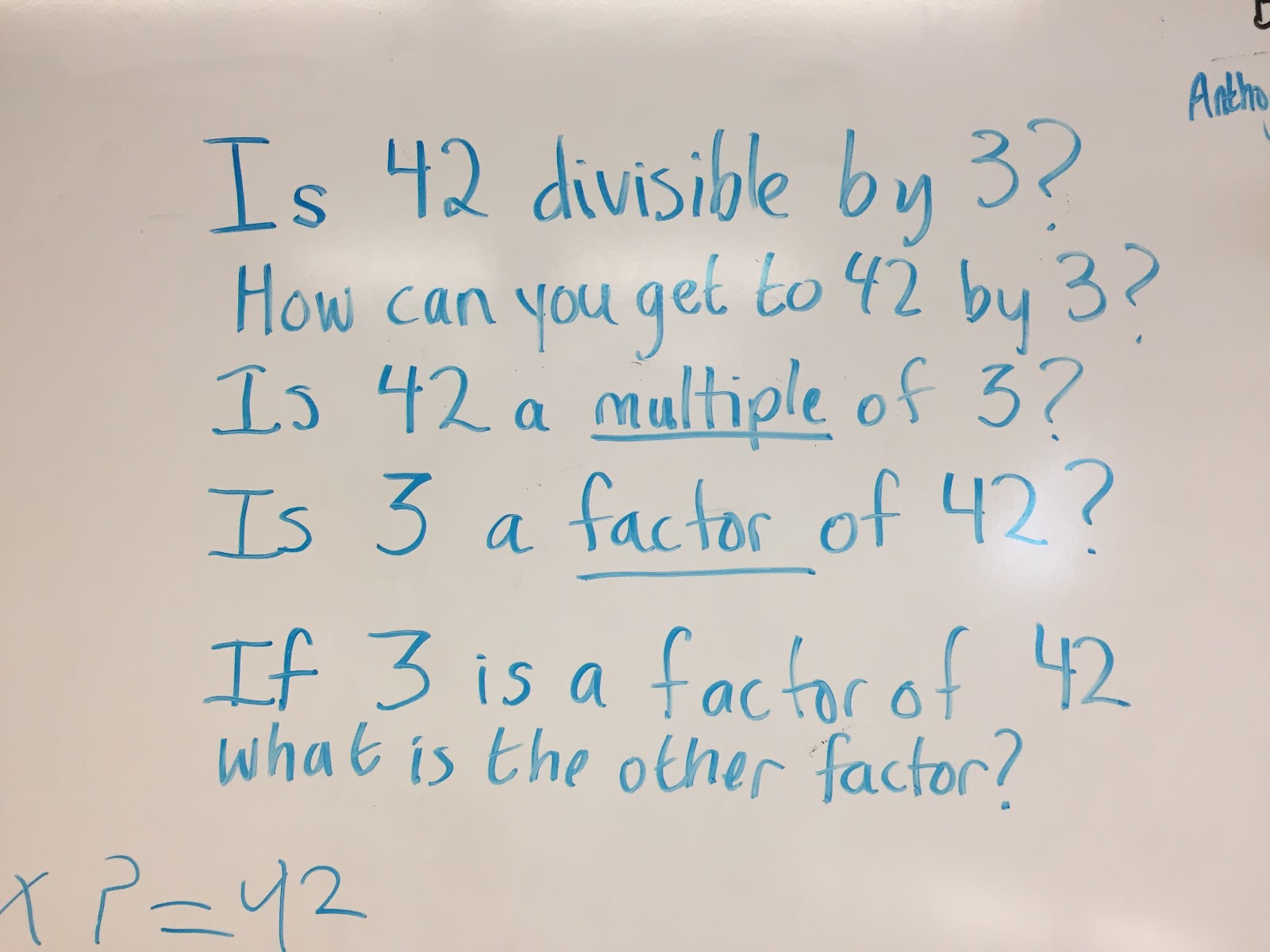

After five minutes of this warm-up, students came to the rug, and Ms. Lynn began their number talk by writing the number 42 on the board. Next to it, she wrote, “Is 42 divisible by 3?”

Student thought quietly and then some began to share ideas. Only a few words had been spoken, though, when Josiah, a Black boy who was sitting, along with two other students, on yoga balls at the edge of the rug, called out, “What does that mean?”

I suggest you pause right here and think for a minute. How would you respond to Josiah’s question? This is the discretionary space, and Ms. Lynn had to decide how to respond.

While you think, I’ll tell you what I observed about Josiah in the few minutes preceding this moment. I had watched him counting by 3s with his partner, and it wasn’t easy for him. He had to stop and think often. His partner would coach him by reminding him of the last number she had said, but she didn’t tell him what his number was. I also observed that he seemed energetic, cheerful, friendly, and easily distracted during the first few minutes of the number talk on the rug.

As Ball does in her address, I’ll list some ways I think teachers might commonly respond to Josiah’s question.

“Josiah, please don’t call out. Raise your hand if you have a question.”

“Who can help Josiah remember what ‘divisible’ means?”

“We’ve been talking about that word for a while now, Josiah.”

Some teachers, having observers in the room, might be embarrassed by both Josiah’s question and his calling out.

Here’s what Ms. Lynn did.

“Good question!” she responded warmly. “What’s another way I could have asked that question?”

Students began to raise their hands and she started a list on the board. The second question on the list was Josiah’s. “How can you get to 42 by 3?” he asked. Although his wording wasn’t mathematically precise, Ms. Lynn wrote it down on the board, because although his wording wasn’t perfect, his thinking was.

After another student offered, “Is 42 a multiple of 3?” Ms. Lynn asked, “Can anyone use the word ‘factor’ to ask the question?” This sparked a few more ideas.

Next Ms. Lynn asked, “How could I ask this question using just math symbols?” One student wrote 3 x ? = 42. Then Zoe came up and wrote 3 x 42 = ?.

“What did Zoe say?” Ms. Lynn asked. “Do you agree or disagree?” Hands went up all over the room.

“Zoe, look how many people are excited to talk about your thinking!” Ms. Lynn said, and Zoe smiled.

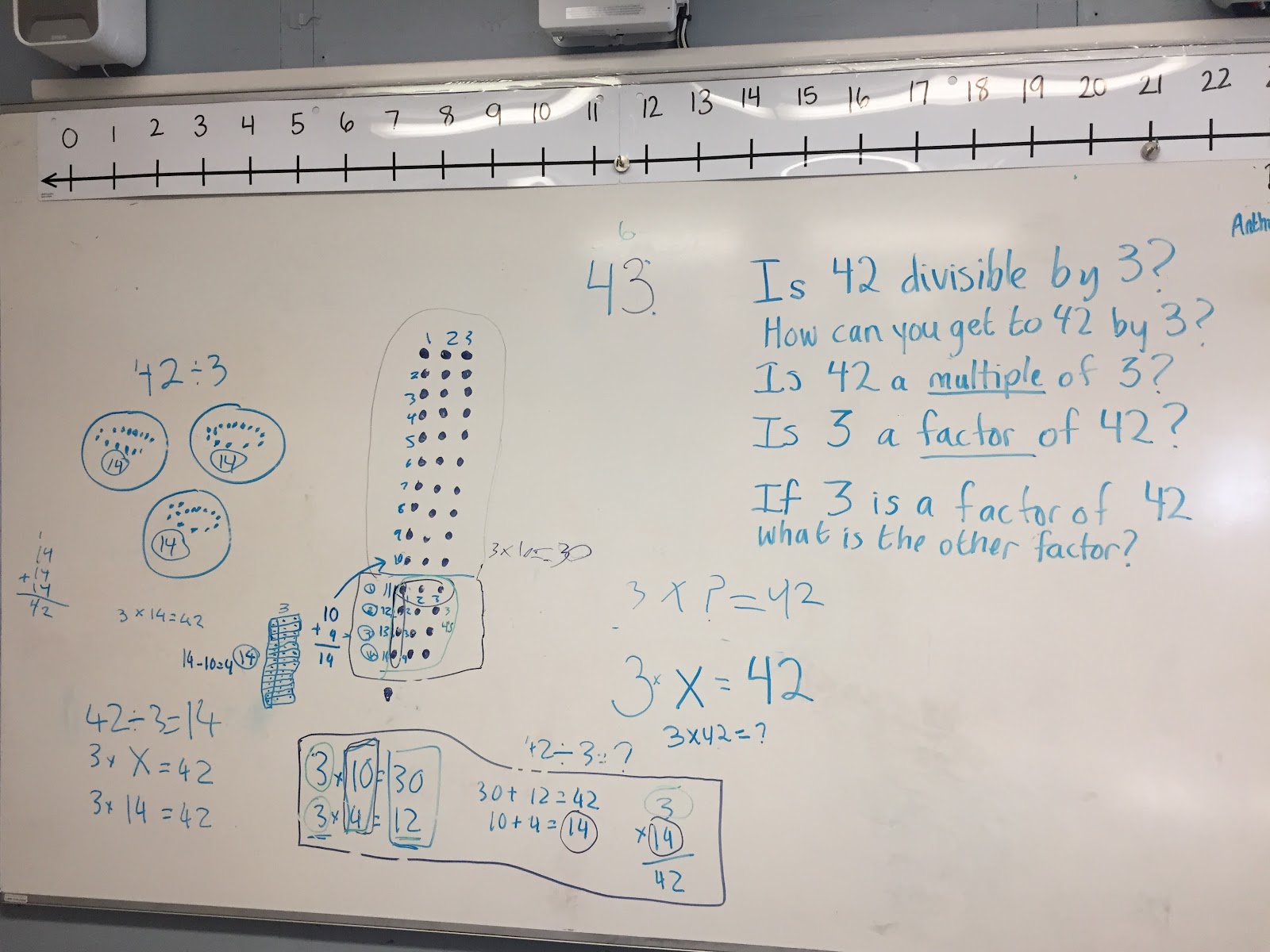

And they were off on a thoughtful conversation about the relationship between multiplication and division in which they drew a variety of models, wrote numerous equations, and thought deeply about the Big Ideas of fourth grade math.

Like Toni, Josiah asked an important question, and by taking him seriously, Ms. Lynn gave him (and other students who might have had trouble remembering what “divisible” means) an entry into the lesson. Josiah’s question showed that he wanted to participate in the math discussion and that he was thinking about the math. That was what mattered, not whether he raised his hand or remembered a mathematical term.

Not only did Ms. Lynn value Josiah’s question, she also leaned into it, figuring out in a matter of seconds how to use it to spark a conversation that was precise in both language and mathematical ideas. She did this again with Zoe’s incorrect thinking, putting the responsibility of finding and explaining the error on the students in her class. Here again, she turned a “mistake” into a springboard for real thinking and discussion.

Here is a picture of what the board looked like at the end of the lesson. (At one point someone asked what would happen if they tried to find out if 43 was divisible by 3, so in this photo the number on the board is 43.)

At one point in the conversation, I was sitting next to Josiah, and he asked, “Can I share the meaning of division?” This is a student who in some classrooms would be in trouble, would be admonished for calling out, and would probably not participate in math class because of a fear of making mistakes. Instead here he was, part of the math conversation, thinking out loud, taking risks, sharing his Black boy brilliance.

*All names in this classroom vignette are pseudonyms.